Bastian Balthazar Bux is a “little boy of ten or twelve,” friendless, bad at school, and referred to by his peers as “screwball” for his habit of telling himself stories out loud. His mother is dead and his father, a dentist, is lost in his own remote planet of grief. One morning on the way to school, Bastian escapes a group of bullies by ducking into a bookshop, whose proprietor happens to be reading a mysterious book, The Neverending Story, beautifully bound in copper-colored silk. Ensnared by its title—“Here was just what he had dreamed of, what he had longed for ever since the passion for books had taken hold of him: A story that never ended!”—Bastian steals the book when the owner goes to answer the telephone, entering into outlawry and one of the most indelible journeys through the mystical in children’s literature.

The outlines of Bastian’s adventures will be familiar to anyone who has seen the 1984 cult classic film made from Ende’s novel. Bastian hides with his newfound treasure in the attic of his school, where he begins to read. The book he has stolen opens with a crisis: the Childlike Empress, the ruler of a magical land called Fantastica, has fallen gravely ill with a mysterious sickness that threatens her life and the health of Fantastica itself, for the Childlike Empress is “the center of all life in Fantastica.” A Fantastican boy about Bastian’s age, Atreyu, is chosen for the all-important quest of finding a savior to cure the Childlike Empress and restore the realm. He is given Auryn, the amulet of the Childlike Empress, to guide him on his quest. Fantastica is also imperiled by the spreading presence of the Nothing, a metastasizing emptiness that swallows up landscapes and peoples alike: “not a bare stretch, not darkness, not some lighter color; no, it was something the eyes could not bear, something that made you feel you had gone blind.”

Atreyu must first traverse the perilous Swamps of Sadness, where he loses his beloved horse Artax. Unprotected by Auryn, Artax is so weighed down by sorrow that he drowns before Atreyu’s eyes. Artax’s death in the film version famously scarred the childhoods of an entire generation; the scene is so upsetting that director Wolfgang Petersen was still countering a persistent rumor that the horse actor died during filming twenty years after the movie came out. (In fact there were two horse actors, both of whom worked with a trainer for months to prepare for the scene, and both of whom survived.) In the book, Artax speaks, expressing his terrible grief to a bewildered Atreyu. “I can’t stand the sadness anymore,” he cries. “I want to die!” Atreyu tries to give Artax Auryn, but the horse refuses it, insisting that Atreyu does not have permission to transfer the amulet to another person and must carry on alone. Atreyu, heartbroken by his loss, reluctantly continues.

As Bastian follows along, he is increasingly implicated in Atreyu’s quest. He is as devastated as Atreyu by the death of Artax; he seems at times to even see what Atreyu sees, to experience what Atreyu experiences as if he is actually present in the Neverending Story. In a moment of great peril, he cries out a warning to Atreyu—and his cry is heard in the pages of the book.

Atreyu reaches the oracle Uyulala with the help of the luckdragon Falkor. But before Atreyu can speak to Uyulala, he must pass through a series of magical gates. One of them, he is told, the Magic Mirror Gate, will show him his true self. The reflection he sees in the mirror is unmistakably Bastian in his attic: “a fat little boy with a pale face… sitting on a pile of mats, reading a book. The little boy had large, sad-looking eyes, and he was wrapped in frayed grey blankets.” And when Atreyu loses his memories as he passes through the final gate, it’s Bastian’s voice once more that crosses over into Fantastica and persuades him to keep going. Atreyu learns that in order to be healed, the Childlike Empress must be given a new name. The catch: no Fantastican can give it to her. Only a human being, Uyulala tells him, has the power to do so, but no human has visited Fantastica in a long time, “for they no longer know the way.”

Bastian, in his attic, thinks that he would gladly help the Childlike Empress if he were able to; he could dream up the most beautiful new name imaginable, if somebody would only show him how to get to Fantastica. But despite increasing evidence to the contrary, he is sure The Neverending Story is just a book. He is afraid to make a fool of himself by asserting that he is truly being called into Fantastica by its pages. Atreyu, assuming his quest has been unsuccessful, persuades Falkor to fly him to the edge of Fantastica to look for its mysterious savior. He falls from Falkor’s back and loses Auryn while flying over the sea, washing up on a lonely beach in a strange country on the verge of annihilation by the Nothing.

It is here, in one of the more extraordinary passages of this extraordinary book, that Atreyu meets Gmork, a werewolf who has been chained up by the princess of the city after she discovered he is in service to the Nothing and was sent to thwart the Empress’s chosen hero from completing his mission and finding Fantastica’s savior. The witch-princess and her ghostly entourage have gone to throw themselves into the Nothing, leaving Gmork awaiting his own fate. Atreyu realizes that, though he is himself without hope, having lost his amulet and his luckdragon, Gmork is the only creature in Fantastica who can tell him where to find its savior.

The Nothing is an indestructible force, Gmork tells Atreyu, that compels Fantasticans to leap into it; but when they are swallowed whole by the Nothing, they emerge into the world of humans as lies:

“[W]hen you get to the human world, the Nothing will cling to you. You’ll be like a contagious disease that makes humans blind, so they can no longer distinguish between reality and illusion [… You] will become delusions in the minds of human beings, fears where there is nothing to fear, desires for vain, hurtful things, despairing thoughts when there is no reason to despair. … [Y]ou too will be a nameless servant of power, with no will of your own. Who knows what they will make of you? Maybe you’ll help them persuade people to buy things they don’t need, or hate things they know nothing about, or hold beliefs that make them easy to handle, or doubt the truths that might save them. Yes, you little Fantastican, big things will be done in the human world with your help, wars started, empires founded…”

It is here that Bastian at last realizes the interconnection between Fantastica and his own world, that the world he lives in is as ill as Atreyu’s, that the people around him have become cynical and resigned to misery, when he himself “never stopped believing in mysteries and miracles,” that the work ahead is to bridge the divide between the world of the fantastical and the world of the everyday; in short, to envision the utopian and to live as though it is already present. It will take more effort on the part of both Atreyu—who survives his encounter with Gmork and is rescued by Falkor—and the Childlike Empress herself, but at last, Bastian is brave enough to give the Childlike Empress her new name, and Fantastica is saved.

The movie—which Michael Ende famously loathed (“A gigantic melodrama of kitsch, commerce, plush and plastic”), going so far as to sue its producers in an attempt to halt its production—ends here, with a rousing and extremely American sequence in which Bastian brings Falkor Earth-side to chase his bullies into the very dumpster where they once forced him to hide.

But the book does not let either Bastian or the reader off so easily. Bastian does give the Childlike Empress a new name, and is transported to her side in Fantastica, where she gives him Auryn—and the task of rebuilding Fantastica by reimagining it. He realizes that inside the amulet is inscribed the motto DO WHAT YOU WISH, which Bastian interprets to mean gives him “permission, ordered him in fact, to do whatever he pleased.” Bastian’s wishes—to be handsome, brave, strong, and admired—generate adventures, creating adversaries for him to conquer and quests for him to triumph over, but with every wish, unbeknownst to him, he loses another memory, and with it his way home.

Bastian, drunk with the power of Auryn, decides to assault the Childlike Empress’s citadel and declare himself emperor of Fantastica. Atreyu and Falkor stop his coronation ceremony, resulting in a battle that destroys the Ivory Tower and sends Bastian fleeing into the wilderness after striking Atreyu down with his sword. His long pilgrimage leaves him with only the memory of his father and of his own name. At last, he realizes that his one true wish is to love, and to be loved, as he is, and he gives up his final memories of himself.

Atreyu and Falkor come to his rescue, promising to complete Bastian’s unfinished stories in Fantastica so that he can return to his own world and begin the work of healing the divide between the everyday and the imaginary. Bastian goes home to his father, where the two finally confront their shared grief over the loss of Bastian’s mother. And Bastian, newly at peace with himself, returns to the bookstore where he stole The Neverending Story, confesses his crime, and learns that the bookstore’s proprietor himself once journeyed to Fantastica.

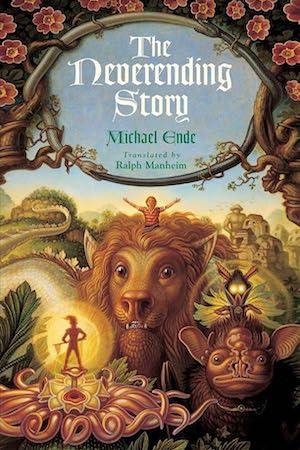

I was around Bastian’s age when I first found The Neverending Story in the tall, shadowy stacks of the grown-ups’ section of my local library. Like him, I was a solitary, bookish child, lost in worlds of my own, incompetent at sports of any kind, suspected of social irredeemability by my peers; like him, I was instantly seduced by the book’s title–a neverending story! What an unimaginable delight! For I read, then as now, with the desperate desire to inhabit a world more pleasurable than the one into which I had been born and was required to endure; books were the one thing that allowed me to forget myself and my ordinary life, depressingly unalleviated by magic and heroic quests and dragons. And like Bastian’s copy of the book, the edition I found was a beautiful object, a hardcover first American edition printed in red and green ink–red for the parts of the book set in the human world, green for Fantastica—whose chapters began with Roswitha Quadflieg’s beautifully illustrated ornamental initials. I fell in love with The Neverending Story in the way only a child can come to love a book, dazzled by its variegated visions of spectacular creatures and a wondrous parallel world, tantalizingly close to our own for any child courageous enough to reach it. I returned to the book many times over the years, but it was not until relatively recently that I thought to learn more about its author.

Michael Ende was born in 1929 in Garmisch, a small town in the German Alps. His father was the surrealist painter Edgar Ende; his mother, Luise, was an autodidact and orphan who read widely in philosophy, literature, and mysticism, and who herself began to paint later in her life. When Michael was a toddler, the Endes moved to Munich, where Edgar Ende’s career briefly flourished, but the changing political climate sent the family into poverty. In 1936, Edgar Ende was labeled a “degenerate” artist by the National Socialist regime and banned from painting altogether. Many of his colleagues and friends were arrested and disappeared. The Endes became dependent on what little Luise could earn, and the marriage deteriorated. Like his character, Bastian, Michael Ende was an academic failure as a child, and his humiliation plunged him into such despair that he contemplated suicide.

The family’s difficulties were compounded by the devastating pressures of the Nazi regime and the Second World War. The Endes managed to keep Michael out of the Hitler Youth by sending him to a military riding school, but he was drafted into the Waffen-SS in 1944 along with all other boys of his age. Michael Ende had already witnessed the 1943 bombing of Hamburg, which occurred while he was in the city visiting an uncle. “It was as though the world was coming to an end,” he said later, in a 1983 interview with German Playboy (!). “I still dream about it now—how we found charred corpses shrivelled to the size of babies. I can still see the army of totally helpless people wandering through the ruins as though trapped in a labyrinth. One of them was carrying a table on his back, which was probably the only thing he could save.” Michael Ende tore up his draft papers and joined a Bavarian resistance unit as a courier until the end of the war.

Ende was profoundly influenced by his schooling under the Nazi regime and his experiences during the war. His body of work is not without its flaws; his first book for children, Jim Button and Luke the Engine Driver, has a Black boy as its central character—nearly unheard-of in 1960s Germany—and is filled with references to the horrors of fascism and its attendant racisms and xenophobias. But to say that its visual depictions of the titular Jim, by the prolific illustrator Franz Josef Tripp, would be unpublishable today is an understatement. Atreyu’s nomadic, buffalo-hunting people, the Greenskins, are unsubtly modeled on the Indigenous tribes of the Great Plains of North America, reflecting a long-standing and troubling German infatuation with stereotypical images of Native Americans; Atreyu himself, brave, stoic, and relentlessly virtuous, strays into the territory of the noble savage. (Atreyu is played in the movie by Noah Hathaway, a white child actor with a liberal application of foundation.) A number of Ende’s views about the essential nature of women and men and heterosexual relationships, as expressed in interviews, are rather tedious.

But Ende was preoccupied with liberation, even if he may have struggled to imagine its potential subjects as people with bodies and experiences different from his own. He resisted the idea that his work should be interpreted through a political lens, but he was explicit in interviews: “In the ancient cultural places of the world there was a temple, a church or a cathedral in its center. From there came the order of life. In every modern big city there is a bank building in its center… I have tried to depict this as a kind of demon cult, where money is something to be prayed to like something sacred. […] It has the character of everlastingness. But if there is anything that is just a purely man-made thing, then it’s money.” And elsewhere: “The victims of our systems are the peoples of the Third World and nature. They have to pay the bill. They get recklessly exploited, so that the system goes on functioning. In order to invest money as profitably as possible, so that capital increases and grows, they have to pay the bill, for, of course, this growth does not come out of nothing.”

In the extended Michael Ende universe, children frequently figure as agents of resistance, in large part because it is particularly difficult to persuade children that their pleasurable activities—play, imagination, storytelling, the construction and exploration of alternative futures—are wasteful. (This idea is fully explored in his 1973 novel Momo, in which a little girl does battle against a grim army of cigar-chomping men in grey who steal time from the unsuspecting adults in her small village. The adults are convinced to enact legislation forbidding unstructured play, arguing that children who are allowed leisure and imagination “become morally depraved and take to crime. The authorities must take steps to round them up. They must build centers where the youngsters can be molded into useful and efficient members of society.” Momo alone remains resistant to the men in grey, and is ultimately able to defeat them by opening their vault and freeing the stolen time.) Fantastica is dependent on the real world, because Fantasticans cannot create new stories; the real world is dependent on Fantastica, because without the world of the creative imaginary, human beings are reduced to cogs in the machinery of capital, deluded by the Nothing and its servants’ misappropriation of the imaginary for the purposes of political repression and senseless consumption. Ende was no stranger to fascist deployment of “fears where there is nothing to fear” and regimes that come to power with the understanding that “when it comes to controlling human beings, there is no better instrument than lies.”

Throughout his journey, Bastian is reminded insistently that his ego is the greatest threat to his own self-realization and the safety of Fantastica. When the centaur Cairon first gives Atreyu the Childlike Empress’s amulet—as Bastian reads along—he explains that “‘Auryn gives you great power… but you must not make use of it. For the Childlike Empress herself never makes use of her power. Auryn will protect you and guide you, but whatever comes your way you must never interfere, because from this moment on your own opinion ceases to count. For that same reason you must go unarmed. You must let what happens happen. Everything must be equal in your eyes, good and evil, beautiful and ugly, foolish and wise, just as it is in the eyes of the Childlike Empress. You may only search and enquire, never judge.” It is when Bastian forgets this equilibrium, when he privileges his own selfish desires—to be seen as a wise, handsome, and brave hero, instead of to share in the future of both worlds—that he causes tremendous harm, both to himself and to Fantastica.

The Neverending Story lends itself easily to a Buddhist reading; Michael Ende was himself fascinated by Zen Buddhism and spent a considerable amount of time in Japan. Bastian must reconcile himself to the deep, life-altering grief of his mother’s death; he must come to peace with himself and learn to love and be loved as he is, flawed and imperfect and still deserving of care; he must set aside the impulses of his ego in favor of more meaningful and mutually dependent relationships with other beings. These are valuable lessons for any person, in any time. But the relationship between Fantastica and the human world has more expansive tools to offer than just a metaphorized exploration of the journey to individual enlightenment.

In this world, in this time, we live surrounded by the degradations of the Nothing. The extraordinary disconnect between the discourse of progress and the lived realities of millions of people, even in the wealthiest nation on earth—an ostensible democracy actively funding and abetting an ongoing genocide, a nation where entire cities have no access to drinkable water, where schools are closing or their libraries are being stripped, where huge swathes of the population have no access to life-saving medical care or any medical care at all, where the right to simply exist in public is denied to trans and queer and unhoused people, a nation with the highest maternal mortality rate in the developed world and the highest child incarceration rate on earth—is a nearly unbearable space to inhabit. We are living in a time of uncontrollable ecological catastrophe, set in motion by a handful of board members and shareholders well aware of the consequences of their greed, that is already rendering whole swathes of the planet unlivable and that will continue to metastasize into unaccountable suffering disproportionately borne by the people least responsible for it. This is a tenuous existence even for those of us who still have access to the exponential privileges of certain kinds of citizenship in certain kinds of countries—those of us born, if you will, into the staterooms on the Titanic.

Cruelty is not a byproduct of the system we live in; it is a constitutive element. We are meant to be productive in these conditions. We are certainly not meant to consider what an ethical life might look like in a world where it is literally impossible to survive—to eat, to work, to play, to build homes, to clothe ourselves, to make a life—without consuming goods produced under circumstances of near-slavery at best and, more often, as a result of ecocide and extraordinary violence. When we choose to be aware of these conditions, to speak them aloud, to confront them with protest, we are tear-gassed and beaten by police and incarcerated. We are told that our grief is unreasonable, that we are inconveniencing others, that we are making fools of ourselves, that we are undeserving of even being seen or heard–I am thinking here of the indelible images of people on their way into the 2024 Democratic convention in Chicago covering their ears and laughing at pro-Palestinian protestors. We may become disoriented by the realization that many who share this present with us are willing to overlook the bloodthirsty viciousness of empire–or may go so far as to actively embrace and abet it–even as they insist they are doing otherwise. And yet despair, a condition which many of us may come to inhabit, is presented to us as a moral failure of which we should be ashamed.

But I would like to propose an alternative theory of despair: despair, it seems to me, is collective grief unrecognized, and grief is the only reasonable response to the world in which we are currently living. Despair is a grief, which means there is something we are grieving; which means there is something we have seen to be grievable. Something we have recognized as real and present. We have come to the abyss and named it for what it is. Despair says: the house is burning down and everyone and everything we love is inside the house. There will be no kitchen renovation. There will be no garden. We will lose so much that we love; we have already experienced losses so enormous as to unmake us. Fantasticans who fling themselves into the Nothing, as Gmork tells Atreyu, may become “despairing thoughts where there is no reason to despair,” but in fact we have many reasons to despair, and even if despair, as Gmork suggests, is a failure of the imagination, there is no reason we cannot navigate that failure together and imagine its alternatives in community. How we grieve shapes how we reimagine the world. If these losses are unbearable, let us learn not how to bear them but how to remake the conditions that bring them into being.

I myself cannot think of despair as a failure of either morality or imaginative faculty; I cannot think of it as any kind of failure at all. I think that shared grief is among the most legitimate and powerful opportunities we have available to us. It is a place where we can agree to come together. Despair means that we have already acknowledged the unbearable present and its nightmarish consequences. We have refused to turn away from the truth; we have named it as what it is. Which means a great deal of work has already been done, and we are open, as impossible as it may seem, to the possibility of alternative strategies for joy and resistance and relationality and home. If despair is the understanding that the world we live in is unbearable—“unbearable,” writes Christina Sharpe, “and entire populations are being forced to bear it anyway”—it can also be the recognition that we have nothing left to lose. The loss of hope is in its own way the ultimate detachment from the demands of the ego.

And when there is no hope, any action is possible. Hopelessness becomes our kinship and our connection: across borders, across walls, across the differences of our bodies and our lives and our experiences. We have come to the Nothing, and it is ours to remake into a Something, which is to say a something else. In our hopelessness, we are still capable of resistance and insistence: resistance to what is, insistence on what is possible. In our hopelessness, the possible is still ours to inscribe upon the present.

We can return to the swamp in which Artax drowns, unprotected by the shelter of the Childlike Empress’s talisman. It is Artax’s grief in the face of unimaginable suffering, the total annihilation of his world, that pulls him under, and it is the shared grief of Bastian and Atreyu, the devastation of loss, that is their first step on the journey together to a newly imagined world, one in which the ultimate guide is not the pursuit of individual happiness but of love and collective liberation. What is a swamp, after all, but a place of transition between the world of water and the world of earth? Think for a moment of the many plants and animals that make a home in that suspended zone, and thrive.

And I am arguing here for the capacious “we” of Fantastica, a “we” that includes all beings, human and nonhuman, the enslaved, the displaced, the imprisoned, the stateless, the millions of people who have already been enduring apocalypse for a long time now. The dreamers, the mad, the abolitionists, the insurrectionists. The queers and the poor, the addicts and the unhoused: a capacious, rebellious, ever-expanding “we,” a “we” where all beings are equal and cherished, human and nonhuman alike. Do what you wish: wish for freedom, and let that wish be a doing that inhabits your every action.

It is not Bastian’s imagination alone that sets him apart from his peers; it is his capacity to name the possible and his willingness to work through the fear of recognizing his part in the future-making project of the story he has entered. It can be quite terrifying, for those of us raised in the embrace of empire, to say what is obvious, which is that the system in which we live protects the very few at the great expense of the many. That our current trajectory, pulled into the depths of the Nothing by the death wish of empire, is more than just unbearable; it is the end of any future in which freedom exists for anyone.

After his failed coronation, once again alone, Bastian wanders lost across Fantastica. He reflects on the trespasses he has committed against his comrades and is consumed by shame. He stumbles into a strange city, where the buildings are “jumbled every which way without rhyme or reason” and the inhabitants are “dressed as if they had lost the power to distinguish between clothing and objects intended for other purposes.” His attempts to speak with the townspeople are met with confusion. He meets a monkey named Argax, who informs him that he has reached the City of the Old Emperors—a squalid, chaotic place of misery and confusion. All the human beings who succeeded in crowning themselves Emperor of Fantastica lose themselves completely in the same instant and are transported to the city, where they remain forever. “Nothing can change for them, because they themselves can’t change anymore.” Bastian understands that he has been given a tremendous gift; Atreyu has thwarted his desire to conquer, and thus saved him from the fate of the other humans who have attempted to assert their own will over the beings of Fantastica. For the Childlike Empress herself does not rule; she “was far more than a ruler. She was something entirely different… She had never used force or made use of her own power. She never issued commands and she never judged anyone… In her eyes all her subjects were equal. She was simply there in a special way. She was the center of all life in Fantastica.” The Childlike Empress’s world is one without borders and thus free of the violence required to maintain them. It refuses rulership. It insists on freedom.

All empires fall. It is up to us to imagine their alternatives. To live as though the future we are dreaming is already named. To be unafraid to answer its call in the dark, and come into a new world of our making. “And joy filled him from head to foot,” writes Ende, when Bastian has finally realized his greatest wish is love. “The joy of living and the joy of being himself… If he had been free to choose, he would have chosen to be no one else. Because now he knew that there were thousands and thousands of forms of joy in the world, but that all were essentially one and the same, namely, the joy of being able to love.”

To join in love, as we are, to recognize that our lives are bound together and our wellbeing is collective, is the ultimate work of liberation; to live as though the world we inhabit is already the world we want it to become, a world with room enough for all of us, a world in which freedom is not a privilege but a component of the air we breathe. The story as we are telling it is the neverending story of the present. There is no other time we will ever have; it is already ours.